The Under-Rower's Way: The Marks That Matter

Part IV

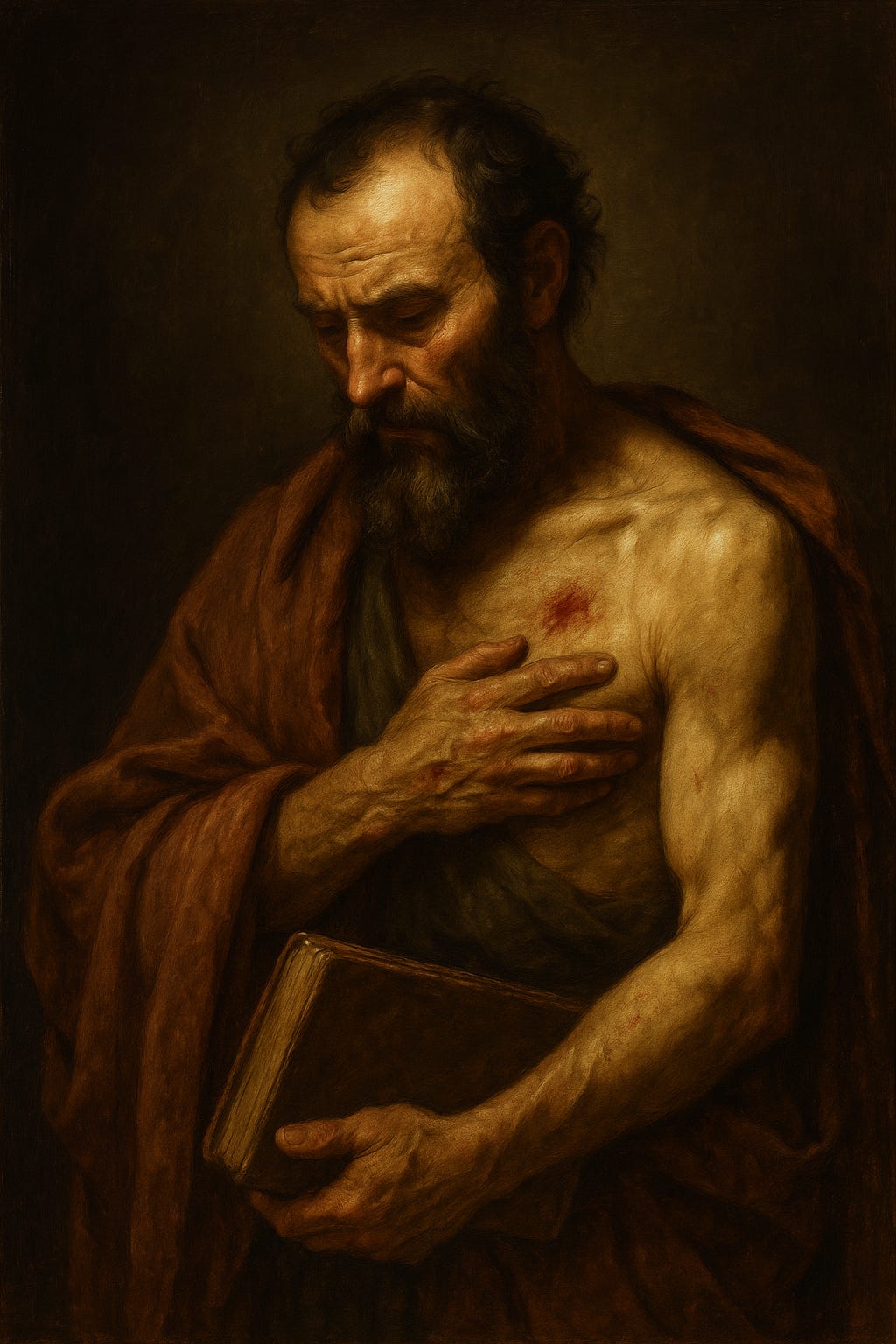

Galatians 6:17 From now on let no one cause trouble for me, for I bear on my body the marks of Jesus.

Paul was undoubtedly familiar with the concept of an apostle well before his Damascus encounter. In classical Greek, the verb apostéllō generally meant to dispatch a fleet, an embassy, or a messenger on an authoritative mission. Epictetus even describes Zeus sending philosophers as his messengers to humanity, underscoring an apostle as one bearing the authority and message of the sender.[1] In Hebrew thought, as reflected in Rabbinic Judaism, an apostle (shaliach) was an authorized representative who acted in legal or financial affairs with the full authority of the sender, carrying credentials that authenticated the task.[2]

Paul’s blinding encounter with Christ on the Damascus Road initiates more than a vocational commissioning, it marks the beginning of a complete reorientation of what it means to be “sent.” Though Ananias names him a “chosen vessel” (Acts 9:15), Paul’s awareness of his apostolic identity does not spring full-grown from that moment. What follows are years of obscurity and interior formation, during which he moves beyond classical or rabbinical models of representation into a distinctly cruciform consciousness. His public recognition in Acts 13 emerges only after this hidden season has done its work. What is being forged is not simply a memory of encounter, but a way of inhabiting authority from below, a life marked by downward mobility and poured-out service.

Here, John Howard Schütz offers a crucial framework. In Paul and the Anatomy of Apostolic Authority, he insists that “Paul had something to say to ‘his’ communities and presumed both his right to say it and his effectiveness in doing so. In that sense authority is presumed.”[3] Yet this authority does not rest on formal office, institutional title, or even self-assertion. For Schütz, authority must be distinguished from leadership and from charisma. Authority, rightly understood, is “the interpretation of power”[4], its orientation, accessibility, and transmission within a community. It is not force, nor persuasion by personality. It is a patterned communication of power, such that others recognize its source and legitimacy within the life of the one who bears it.

Schütz draws on the Roman concept of the auctor, not merely an initiator, but one whose very being guarantees the legitimacy and fruitfulness of an undertaking.[5] In this light, Paul’s apostolic life becomes a form of interpretation. His proclamation of the gospel is inseparable from the way he inhabits weakness, suffering, and servanthood. His self-designation as hypēretēs, or under-rower (1 Corinthians 4:1), is not rhetorical flourish. It signifies his refusal to assert authority from above and his conscious decision to serve from below. His life bears interpretive weight. It is his scars, not his status, that validate his vocation.

As Schütz notes, “power alone has no legitimacy, no mandate, no office.”[6] What transforms power into authority is precisely the act of interpretation, the way it is embodied, communicated, and shared. Paul's authority, then, does not rest in a formal office; it emerges from a life that interprets Christ’s own kenotic descent. He becomes not only a herald of the gospel but its living exposition.

Central to grasping the meaning of apostleship is the self-disclosure of Jesus, the Incarnate Son, who enters human history explicitly to reveal, to exegete, the Father. John plainly affirms this revelation: "No one has seen God at any time; the only begotten God who is in the bosom of the Father, He has explained (exegeted) Him" (John 1:18 NASB). This exegesis is not limited merely to words or teachings; it includes the entirety of his self-emptying life culminating at the Cross, the apex of revelation and glorification. Athanasius articulates this clearly: the "apparent degradation of the Word" is precisely "his apparent degradation through the cross." The humiliation and degradation experienced by the Son at Calvary is not merely kenotic self-emptying or humiliation for its own sake; it is precisely the highest point of revelation, the ultimate disclosure of God himself in the incarnate Word.[7]

John Behr clarifies Athanasius’s meaning further, emphasizing that Athanasius does not substitute the "scandal of the cross" with another scandal. Instead, Athanasius closely aligns incarnation and cross: it is only "as 'the one who ascended the cross' that we know the Word of God, for the more he is mocked, the more his divinity is made manifest."[8] For Athanasius, the Incarnation is inseparable from the crucifixion. God's revelation occurs precisely in the act most mocked and rejected by human wisdom, yet simultaneously most expressive of divine power and goodness.

This self-disclosure reaches beyond mere individual manifestation. The late John Zizioulas offers a complementary theological insight, affirming that Christ cannot be adequately understood merely as an individual, historically distinct from his body, the Church. Rather, Christ exists relationally, in communion, defined pneumatologically. According to Zizioulas, Christ’s identity and truth are established by the Spirit, who not only bridges the gap between the believer and Christ but constitutes Christ’s presence within the community. He insists that "Christ does not exist first as truth and then as communion; He is both at once."[9] Christ’s incarnation and cross are not isolated events, disconnected from the communal life they create. Instead, through the sending (apostello) of the Son and subsequently the Spirit, humanity is invited into the perichoretic fellowship of the Trinity itself, into relational communion that defines divine and human existence.

Apostolic ministry, then, emerges naturally from this seminal revelation. To be sent as Christ’s apostle is fundamentally to proclaim the reality unveiled in Christ's incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection. Apostolic proclamation invites all humanity to the divine Table, to participation in the life of the Father, Son, and Spirit, who draw human persons into a communal life of mutual love, service, and union, in whom "we live and move and have our being" (Acts 17:28).

Yet this apostolic proclamation is never simply a call to doctrinal assent, it is fundamentally an invitation into the shared divine life revealed by Christ. To understand fully what it means to be sent, we must grasp the relational reality at the heart of God’s own being. The concept that best illuminates this is perichoresis, the mutual indwelling and reciprocal presence that characterizes the relationship within the Triune God, a concept foundational for a genuinely apostolic consciousness.

Central to understanding apostolic identity is the recognition of perichoresis, the mutual indwelling and reciprocal presence that characterizes the relationship within the Triune God. Perichoresis, from the Greek περιχώρησις meaning "interpenetration," first emerges explicitly within Trinitarian theology through John of Damascus, building upon earlier developments by Gregory of Nazianzus and Maximus the Confessor. These earlier theologians initially used the term to describe the interpenetration of Christ’s two natures, a dynamic later extended to describe the mutual indwelling of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.[10]

D. Glenn Butner Jr. emphasizes that perichoresis refers specifically to the mutual presence and coinherence of the three divine persons, often illustrated through metaphors of motion, spatial relationships, and the unity of love, consciousness, and will.[11] Michael Horton notes further that this mutual indwelling is vividly portrayed in John’s Gospel, where Jesus speaks intimately of existing eternally in the bosom of the Father, and explicitly about mutual sharing within the divine community (John 1:18; 14:10; 17:5). Horton clarifies that this profound relational unity is not merely functional cooperation, as in some theological interpretations, but is grounded in an essential unity of being.[12]

Gilles Emery deepens this understanding by stressing that the Trinity is fundamentally a revealed mystery, inaccessible apart from divine self-disclosure in history. Through the historical events of the Incarnation and Pentecost, the Trinity becomes known not as abstract doctrine but as a lived reality in which God personally and relationally gives Himself to humanity.[13] This historical manifestation undergirds our knowledge of God, inviting believers into the intimate communion of Father, Son, and Spirit.

Sharon Tam and Leighton Ford offer an evocative image of perichoresis as a divine "circle dance," highlighting the active, relational dynamics within the Trinity. This metaphor captures the continuous mutual giving and receiving, permeating and enveloping, that defines the inner life of God. In this divine dance, each person of the Trinity remains distinct yet fully participates in the life of the others.[14]Catherine Mowry LaCugna eloquently describes this dynamic as each divine person irresistibly drawn into and receiving existence from the others, without blurring individuality or imposing separation, sustaining a communion of love and mutual indwelling.[15]

Paul’s sense of being an apostle wasn't something he wore as a title. It was deeply personal, shaped by his encounter with the living God. When Paul speaks about being an apostle, he's not talking about a status he's earned or a position he occupies. Instead, he's describing who he is at his core: someone called and captured by Christ.

Some modern philosophers, particularly within the existential and phenomenological tradition, shed light on Paul’s experience by helping us see how moments of radical reorientation involve not merely psychological crisis but an ontological summons. In Being and Time, Heidegger describes the call of conscience (Ruf des Gewissens) as that which “summons Dasein’s Self from its lostness in the ‘they.’”[16] The caller, Heidegger insists, is marked by a “peculiar indefiniteness”—it resists all objectification or familiarity. It does not declare its name or origin; it simply calls. “That which calls the call, simply holds itself aloof from any way of becoming well-known… and this belongs to its phenomenal character.”[17] This summons cannot be coerced and does not seek recognition; it is heard only as call. In that light, Paul’s Damascus encounter might be read not only as an historical-theological moment, but as an existential rupture, one that dislocates him from his previous self-understanding and places him under a demand that reconfigures his entire mode of being.

This kind of call doesn't simply tell us what to do; it reshapes who we are. Paul experienced this with unmistakable clarity, especially as he recounts it in Galatians. He turned away from a life that, in retrospect, was no longer truly his own, and entered into a way of being entirely reoriented around the gospel. His identity as an apostle was not conferred by others, nor did it emerge from communal consensus. It was something deeply personal, an identity shaped by divine authority, not the opinions of others (Gal 1:12; 2:2; 2:20).[18]

Phenomenologically speaking, Paul's apostolic consciousness emerges not from conceptual theology or institutional privilege, but from lived embodiment and radical existential restructuring. The term hypēretēs, the under-rower, captures this precisely: Paul places himself at the bottom bench of the vessel, not wielding hierarchical power, but rowing quietly beneath the surface, propelled by the perichoretic life he has witnessed in Christ. This sets a pattern: apostleship becomes first-person experience—rooted in humility, sustained by divine presence, shaped by a consciousness overshadowed by Christ's own self-giving kenosis.

When Paul “knows” the gospel, he isn’t speaking of mere intellectual understanding. His knowledge arises from embodied experience. French philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty clarifies this point profoundly. Merleau-Ponty argues that the body isn’t simply a collection of parts we perceive objectively. Rather, our bodies provide us a unified, primary awareness of ourselves, one that precedes any abstract thought. According to Merleau-Ponty, our bodies don’t relate to the world through objective distances; instead, our bodily existence is fundamentally intertwined with the world itself. We don't just observe reality—we participate intimately in it, engage actively with it, and make sense of it through bodily interaction. Merleau-Ponty describes this vividly: “The synthesis of one’s own body is therefore, by the same token, a synthesis of the world and a synthesis of the body in the world.”[19]

When Paul says, "I bear on my body the marks of Jesus" (Galatians 6:17), he reveals something essential about how we come to know Christ. These marks, stigmata, aren't just figurative or symbolic. Paul carries actual scars; lasting reminders of physical suffering endured precisely because of his faithfulness to Christ. Our bodies, after all, teach us things our minds alone cannot grasp. Every wound, every hardship Paul endured was not only deeply painful but also strikingly humbling. Paul’s body and his psyche carry the lessons of suffering, shaping his knowing and deepening his awareness of Christ's own humility and self-emptying.

This kind of embodied knowing leaves little room for pride. Paul doesn't boast in his title of apostle; instead, he bears witness through vulnerability and quiet strength. His letters are devoid of arrogance, empty bravado, or the toxic displays of authority so prevalent in some contemporary church contexts, where charisma or popularity are mistaken for spiritual authenticity. Paul never “lords it over” anyone, even though he unquestionably possesses apostolic authority—authority he exercises sparingly, primarily for correction and restoration rather than control or domination.

It seems to me Paul’s genuine authority grows directly from the humility learned in suffering. The wounds on his body are mirrored by marks on his soul. These marks shape how he leads, serves, and loves. They embody his apostolic grace, teaching us that true leadership isn't rooted in charisma or confidence, but in the humility and endurance born from authentic, lived encounters with Christ.

In this way, Paul’s entire being, body and mind, is deeply shaped by his personal journey of suffering and faithfulness. His knowing isn't abstract; it emerges directly from embodied experience, forming an apostolic identity that serves from below, marked by compassion rather than control, humility rather than hubris.

Paul’s apostolic knowledge reflects exactly this kind of embodied participation. His identity as an apostle isn’t theoretical or distant; it is woven into his actual physical life, marked by suffering, endurance, and compassion. For Paul, knowing Christ involves actively experiencing Christ’s own humility and exaltation. His apostolic consciousness emerges from these lived realities, shaping how he ministers, serves, and embodies the gospel he proclaims.

Interestingly enough, both Carl Jung, the father of Analytic Psychology, and Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner affirm a deep unity between body and psyche, even though they come from different disciplines. Jung understood the psyche as a self-regulating system closely akin to the body. He argued that the psyche isn’t just the mind or thoughts; it is our whole life, including unconscious complexes and archetypes shaping who we are and how we live. For Jung, our psyche is part of our living reality, not separated from the body but intimately connected, like self‑regulating organs in a living organism.³

Karl Rahner, in his theological exploration of symbol, proposed that the body is the living expression of the soul. The body is not a mere shell, but the soul’s actuality in material form. In Rahner’s view, the body is a “symbol of the soul,” revealing our inner life outwardly. The physical becomes the frame through which spiritual reality is made present and intelligible.⁷

Here is where they overlap in meaningful ways: Jung sees psyche and body as deeply interwoven, where the unconscious speaks through dreams, imagery, and bodily symptoms. Rahner affirms that our embodied life is itself symbolic, revealing the soul and pointing toward God. In both views, the divine or the unconscious is not separate from our physical experience but is interwoven within it.

When we bring this into Paul’s formation as apostle, particularly as one who bears the marks of Christ, these insights converge. Paul’s suffering, his scars, his endurance, all bear witness not just to doctrine but to embodied revelation. His identity as hypēretēs, an under‑rower, is shaped by his body as much as by his spirit. He isn’t claiming authority; he’s embodying it. His wounds and his humility speak louder than any title.

This psychospiritual unity, body and soul dynamically intertwined, echoes both Jung’s insight into the unconscious body‑mind connection and Rahner’s theological affirmation that our bodies are symbolic of our souls and of God’s self‑presence. In Paul’s case, his embodied experience becomes the clear locus (focal point) of apostolic authority, not a claim he makes, but one he lives.

Some readers might question whether apostolic authority can truly be grounded in personal, lived experience rather than formal appointment or doctrinal correctness. However, Paul's own writings strongly affirm that the authenticity of his apostleship lies precisely in the scars and trials he carries (Galatians 6:17), and in the suffering and weakness through which Christ’s power becomes evident (2 Corinthians 11:23–30; 12:9). While Paul clearly states his apostolic calling explicitly (Romans 1:1; Galatians 1:1), his authority’s genuine validation rests not in titles, status, or self-promotion, but in a life transparently shaped by the very gospel he proclaims.

This apostolic formation aligns with existential authenticity. When Paul expresses profound perplexity over the Galatians (Gal 1:6) or pronounces judgment on false teachers (Gal 1:8–9), he is not defending personal status or prestige; he is affirming the gospel as the defining axis of his very being. Paul's conscience recognizes Christ’s call as integral to his own existence. To deny this call would be, in existential terms, an act of self-betrayal—what Kierkegaard describes as the despair of not willing to be oneself before God. Conversely, obedience to this call represents authentic selfhood, what Paul Tillich refers to as the “courage to be,” aligning one's life decisively with divine grace. Paul’s overwhelming identification as an under-rower is not mere metaphorical decoration but an existential orientation. His ministry never sought to ascend hierarchical heights but always descended into the depths of humble service, propelled from below by the perichoretic dynamic of self-emptying love.

Paul’s identity as an under-rower invites us deeper still, drawing us toward the all-too-real tensions he describes vividly in 2 Corinthians 4, 'afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not despairing.' How does one embody this paradoxical resilience, experiencing life's crushing pressures yet remaining inwardly unbroken? In our next and final segment, we’ll explore how Paul's transparent vulnerability, held in tension with unwavering trust, reveals the heart of authentic ministry and offers wisdom for our own struggles with life's complexities.

[1] W. C. Robinson, “Apostle,” in The International Standard Bible Encyclopedia, Revised, ed. Geoffrey W. Bromiley (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1979–1988), 192.

[2] Robinson, "Apostle," 192.

[3] John Howard Schütz, Paul and the Anatomy of Apostolic Authority, ed. C. Clifton Black, M. Eugene Boring, and John T. Carroll, The New Testament Library (Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2007), 8.

[4] Schütz, Anatomy of Apostolic Authority, 14.

[5] Ibid., 15. Schütz draws on classical usages of auctor to describe the one whose own life becomes the source of legitimacy for the community’s shared commitments.

[6] Ibid., 9.

[7] Athanasius, On the Incarnation, trans. John Behr, vol. 44a, Popular Patristics Series (Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2011), 36.

[8] John Behr, "Introduction," in On the Incarnation: Translation, ed. and trans. John Behr, vol. 44a, Popular Patristics Series (Yonkers, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 2011), 37.

[9] John D. Zizioulas, Being as Communion: Studies in Personhood and the Church, vol. 4, Contemporary Greek Theologians (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1985), 110–112.

[10] Thomas O’Loughlin, "Perichoresis," in The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church, ed. Andrew Louth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2022), 1483.

[11] D. Glenn Butner Jr., Trinitarian Dogmatics: Exploring the Grammar of the Christian Doctrine of God (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2022), 227.

[12] Michael Horton, Pilgrim Theology: Core Doctrines for Christian Disciples (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2012), 97.

[13] Gilles Emery, The Trinity: An Introduction to Catholic Doctrine on the Triune God, ed. Matthew Levering and Thomas Joseph White, trans. Matthew Levering (Washington, D.C.: Catholic University of America Press, 2011), 1–2.

[14] Sharon Tam and Leighton Ford, The Trinitarian Dance: How the Triune God Develops Transformational Leaders (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2015).

[15] Catherine Mowry LaCugna, as cited by Sharon Tam and Leighton Ford, The Trinitarian Dance, 2015.

[16] Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, trans. John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson (New York: Harper & Row, 1962), 320 (German pagination: §57). Kindle loc. 9090.

[17] Heidegger, Being and Time, 320–21; Kindle loc. 9090–9105.

[18] Study connecting Heidegger’s concept of conscience with Paul's calling, specifically in the Letter to the Galatians (cf. Gal 1:12; 2:2; 2:20). https://verbumetecclesia.org.za/index.php/ve/article/view/3150

[19] Christopher Macann, Four Phenomenological Philosophers: Husserl, Heidegger, Sartre, Merleau-Ponty (London: Routledge, 1993), 176.