Therefore Thomas, who is called Didymus (“The Twin”), said to his fellow disciples, “Let us also go, so that we may die with Him.” John 11:16 Legacy Standard Bible

We are living in an age of fragmentation—where certainty feels elusive, where long-held foundations of meaning seem to be slipping away, and where the question “Who am I?” echoes louder than ever. The structures that once shaped our identities—family, faith, community, even history itself—are increasingly contested, leaving many struggling to define themselves in a world where everything feels fluid, unstable, and subject to revision. Some respond by doubling down on ideology, clinging to whatever certainty they can find. Others embrace detachment, resisting commitment to any belief, identity, or truth claim. And many find themselves caught in between—longing for something solid but unwilling to embrace illusions of false certainty.

We see this crisis of identity playing out everywhere—socially, politically, spiritually. A world saturated with information yet starving for wisdom. A culture that demands instant clarity but does not give space for real formation. Faith communities that often punish doubt rather than allow it to do its necessary work. In the midst of this, many are left asking: what does it mean to believe? What does it mean to trust? How do I know what is real? These are not just abstract philosophical questions; they are deeply personal. And they are not new.

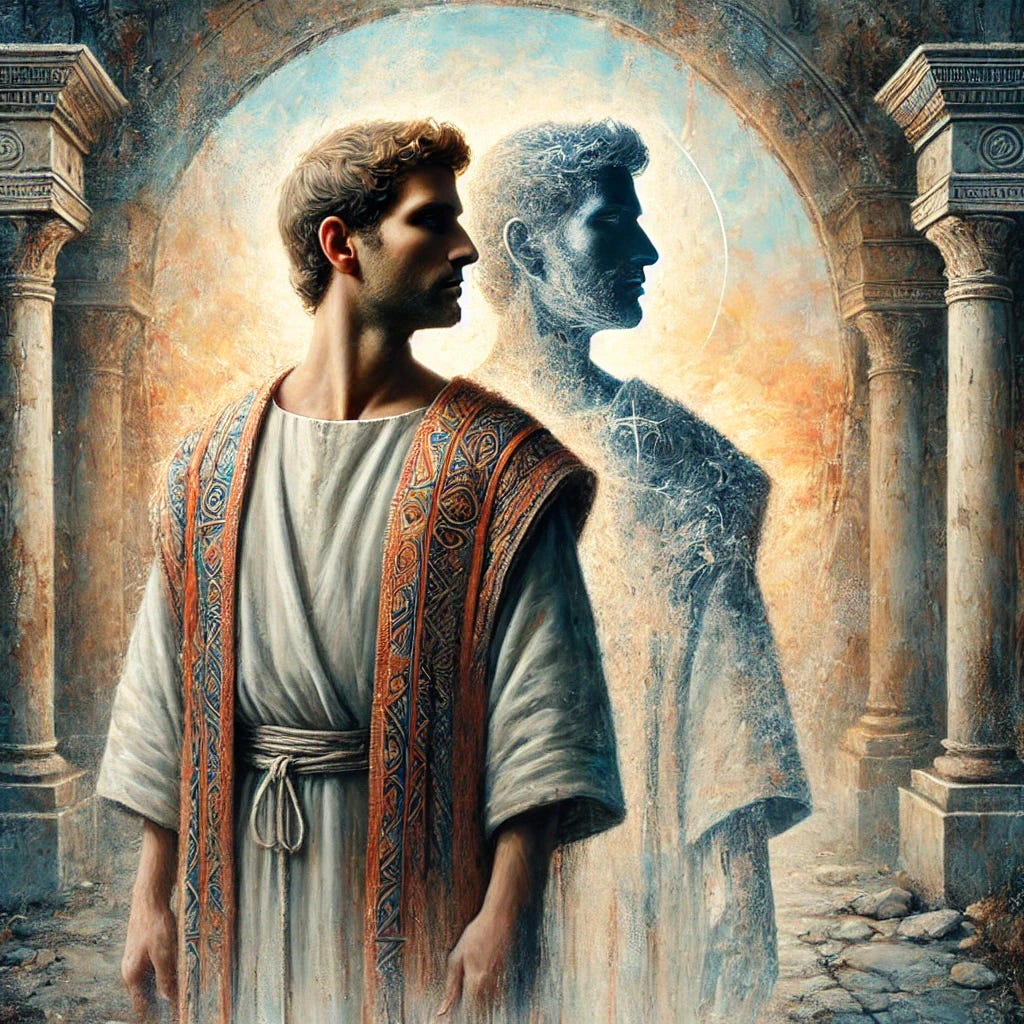

The struggle to believe—to hold faith in the tension between doubt and certainty—is as old as humanity itself. Every generation has wrestled with it. And in the Gospel of John, we find a disciple who embodies this journey: Thomas, the one called “the Twin.” His story is not just about skepticism; it is about the process of faith itself—the movement from uncertainty to conviction, from hesitation to recognition.

But John is not only writing about Thomas; he is writing for a community in transition—a people caught in their own space of uncertainty, wrestling with how to move forward when the structures that once gave them stability have been stripped away.

By the time this Gospel was composed, the followers of Jesus were no longer part of the synagogue. They had been cast out, severed from the religious life and communal belonging that had once defined them. This was more than just a theological shift—it was an existential crisis. To be expelled from the synagogue meant not only a loss of religious identity but a rupture in family relationships, social standing, and cultural legitimacy. Everything familiar was behind them, yet the future remained uncertain. They were a people in liminality, standing at a threshold between what was and what would be, needing something powerful enough to pull them through.

This is where John’s Gospel speaks so strikingly to them—and to us. John does not simply tell them to look backward for their identity; he writes a Gospel that is thoroughly eschatological, summoning them toward the future. His Jesus is no ordinary teacher or prophet—he is the eternal Logos, the one who was with God in the beginning and who remains sovereign over history. He is not only the Resurrected One; he is the Eschaton itself, the Future breaking into the present, calling his people forward. John’s Gospel is a Gospel of movement—not a nostalgia for the past but a summons toward what lies ahead. Jesus, the Logos-made-flesh, is not just offering them reassurance; he is calling them beyond their crisis, beyond their fear, into a reality that is still unfolding.

John’s community needed to hear this. They were not only grieving what they had lost; they were struggling to make sense of the unfamiliar space they now inhabited. If their faith was to survive this rupture, they needed a vision that was large enough to hold them, strong enough to sustain them, and compelling enough to pull them forward. And this is precisely what John gives them—a Christ who is not just present but ultimate, a Christ who calls them not just to believe but to become.

It is in this context that Thomas’s story takes on its full significance. He is not just a disciple who struggles to believe; he is a mirror of the community’s own struggle. His journey is their journey. His questions are their questions. His movement from doubt to confession is the very movement they are being invited to make. And in John’s hands, this is not just about Thomas—it is about every follower of Jesus who has ever stood at the edge of uncertainty, longing for something real.

John is not just telling Thomas’s story. He is telling ours.

Thomas the Twin: A Voice in John’s Gospel

In the Gospel of John, Thomas is more than a name on a list—he is given a voice, a presence, and a journey. Unlike the Synoptic Gospels, where Thomas is mentioned only in passing, John deliberately shapes him as a character who speaks, questions, wrestles, and ultimately arrives at the most personal confession of Jesus’ identity. This is not incidental; John is doing theology through narrative, and his decision to give Thomas a voice signals something essential regarding faith, identity, and the nature of human encounter with the divine.

To be given a voice is to be given significance. It means being drawn into the story as a participant, not merely an observer. Existentially, a voice is an assertion of self—a declaration that one, that you exist, that your questions, doubts, and struggles are not irrelevant. Ontologically, to speak is to engage with reality, to take up space in the unfolding drama of meaning. And theologically, John’s inclusion of Thomas’s voice invites you and me into an intimate process of faith—one that does not require passive acceptance but allows room for honest engagement.

John gives Thomas a voice because Thomas represents a necessary dimension of belief: the faith that struggles, the faith that questions, the faith that seeks clarity before surrendering to mystery. He is not positioned as an antagonist to faith but as one who must move through the difficulty of uncertainty before he arrives at full recognition. This is why John highlights Thomas—not simply to contrast doubt with belief, but to show how belief is formed in the crucible of genuine encounter.

If John gives Thomas a voice, he also gives him presence—a way of being in the world that is fully engaged, fully known. Presence is more than mere existence; it is about inhabiting reality, stepping forward rather than retreating into the background. In John’s Gospel, Thomas does not merely speak; he asserts himself, insists on his own way of engaging with truth, and refuses to be a passive recipient of someone else’s experience. His presence is not one of quiet assent but of active seeking, of refusing to settle for secondhand belief. This is not defiance but a demonstration of what it means to search with integrity.

This question of presence is particularly urgent in our time. In a world that often reduces human experience to data points, online avatars, and curated versions of reality, the question of what it means to be—to have a meaningful presence—presses upon us. Many find themselves dislocated, uncertain of where they belong or how to inhabit the world in a way that is both authentic and recognized. John’s Gospel speaks directly to this crisis, for it is a Gospel of presence—God made flesh, dwelling among us, entering the human condition in its fullness. Thomas, in his insistence on seeing and touching, embodies a yearning for real encounter, for something beyond abstraction. His presence in the text, therefore, is not incidental; it reflects the deep human need to experience truth in a tangible way, to know that we are seen, heard, and held.

Yet John does not only give Thomas a voice and a presence; he gives him a journey. John will make clear that Jesus is the journey, the hodos[1], the way itself. For Thomas, the way is not a neatly marked path; it is a struggle, a movement through uncertainty toward recognition. When Thomas asks, “Lord, we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?” (John 14:5), he is articulating not just his own uncertainty but the universal human condition. We are all in search of the way—how to live, how to believe, how to move forward in a world where the next step is often unclear.

Jesus does not answer with a set of directions, nor does he offer a roadmap. He answers with himself: “I am the way, and the truth, and the life” (John 14:6). The journey is not about certainty; it is about relationship. It is not about a destination in the conventional sense, but about walking with the one who is both origin and end, beginning and fulfillment. Thomas’s story is a mirror of this reality—his movement from doubt to confession is not simply about intellectual assent but about encounter. His journey does not culminate in having all his questions answered; it culminates in standing before the risen Christ and seeing, at last, that the journey itself was leading him to My Lord and my God (John 20:28).

John’s Gospel is not just inviting us to consider Thomas’s journey; it is calling us into our own. The crisis of faith, the longing for presence, the struggle to find the way—these are not peripheral concerns, nor are they unique to Thomas. They are deeply embedded in what it means to be human. In giving Thomas a voice, a presence, and a journey, John extends an invitation: to engage, to wrestle, to walk forward even in uncertainty, knowing that the way is not something we achieve but someone who calls us by name.

Subtle yet deliberate, John’s theological artistry with Thomas matters because it speaks directly to his audience—those who, like Thomas, must believe without seeing. His struggle is their struggle; his questions are their questions. By giving Thomas a voice, a presence, and a journey, John extends an invitation not only to the first-century community but to every one of us who has ever felt torn between certainty and uncertainty, who has ever longed for evidence, who has ever wrestled with the unseen. John is not just telling Thomas’s story; he is telling ours.

John Is Being Intentional And Deliberate

John’s Gospel deliberately calls Thomas “the Twin” (John 11:16; 20:24; 21:2), offering no further clarification about who his twin was or why this designation is repeated. Unlike the other disciples, whose identities are tied to their family, profession, or place of origin, Thomas is defined by his relationship to another—but that other person is never named. This omission forces us to consider whether John is pointing beyond a biological fact to something deeper. If Thomas is always named in relation to someone else, what does that tell us about how he saw himself? How does being “the Twin” shape his experience of faith, doubt, and belief? Contemporary psychological research on twin identity provides insight into how deeply such a designation can affect one’s self-perception. But even for those of us who are not twins, the core issue remains: how do the relationships and labels that define us shape our understanding of who we truly are?

What does it mean to be called “the Twin” when no other name is given? In the ancient world, names did more than distinguish individuals—they carried significance, shaping identity and destiny. Thomas, whose name in both Hebrew (tō˒m) and Aramaic (tō˒mā˒) means “twin,” is unique among the disciples. Unlike Simon Peter, James, or John, he is not identified by his father, his trade, or his homeland. Instead, John’s Gospel repeats the phrase “Thomas, called Didymus”—an insistence that this man’s identity is tied to another. But if John never tells us who that other person is, perhaps we are meant to focus on Thomas himself. If his entire life has been shaped by being part of a pair, what happens when he has to stand on his own? If his sense of self has always been intertwined with another, how does that affect the way he navigates faith, belief, and certainty?

John presents Thomas as a disciple who wrestles with these very tensions. He is the one who speaks when others are silent, yet he is also the one most in need of tangible proof. He is bold and hesitant, committed and uncertain, loyal yet reluctant. His story is not one of simple doubt, but of a man caught between different forces, pulled between conviction and hesitation. He declares, “Let us also go, that we may die with him” (John 11:16), yet later refuses to believe unless he sees and touches Jesus’ wounds (John 20:25). He questions, “Lord, we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?” (John 14:5), yet ultimately makes the most profound confession of Christ’s identity in all the Gospels: “My Lord and my God!” (John 20:28).

Perhaps John’s insistence on calling him “the Twin” is not just a detail of his biography but a clue to understanding his journey. If Thomas’s identity was shaped by always being part of a pair, then his movement toward faith required a separation, a standing alone in belief. John does not simply present Thomas as a doubter—he gives us a portrait of faith in process, a faith shaped by questioning, by searching, by both presence and absence. And in this, Thomas becomes a mirror for us. For those who have ever struggled with who they are, with how they belong, with how to reconcile faith and doubt—his story is not just his own. It is ours.

Andreas Köstenberger notes that "Thomas" is not attested in literature before John's Gospel, while "Didymus" (Greek for "twin") was already in use as a proper name[2]. This suggests that John is doing something intentional with this repeated designation. Unlike the Synoptic Gospels, where Thomas appears only in lists of the apostles (Matt. 10:3; Mark 3:18; Luke 6:15), John gives him a voice, a struggle, a journey. Thomas is not simply a disciple; he is a man navigating the tensions of faith and uncertainty, presence and absence, commitment and hesitation.

Perhaps John’s insistence on calling him "the Twin" hints at something deeper than mere biological fact. What if the Gospel writer is inviting us to see an inner conflict within Thomas himself—a man caught between competing forces? He is the one who boldly declares, “Let us also go, that we may die with him” (John 11:16), yet later refuses to believe in the resurrection unless he sees and touches Jesus’ wounds (John 20:25). He is the disciple who questions, “Lord, we do not know where you are going. How can we know the way?” (John 14:5) yet later proclaims the most definitive confession of Jesus’ identity in all the Gospels: “My Lord and my God!” (John 20:28).

Thomas’s story is not one of doubt alone—it is about identity, tension, and transformation. He is a disciple who wrestles with faith, yet in doing so, arrives at a belief deeper than those who accepted without question. John gives us a disciple who is seeking integration, moving from uncertainty to conviction, from questioning to full recognition of who Jesus is.

What if Thomas’s journey is meant to reflect something about our own? What if his movement from hesitation to faith is not a weakness but a pathway to genuine belief? In this article, we will explore Thomas’s internal journey, the significance of his "twin" identity, and what his struggles reveal about the nature of faith itself. Because in his story, we might just find our own.

The Formation of Identity in Twins

Psychologists Amani and Shariatipour note that "the relationship between twins is one of the most intimate interpersonal bonds"[3] and that for identical twins, this bond is even closer than for non-identical twins. While early attachment primarily focuses on the primary caregiver, research suggests that at around 36 months, this attention shifts to the twin as an easily accessible social companion[4]. From this point onward, twins experience partnerships, interactions, and trust through play, fostering a secure bonding relationship[5].

This developmental shift is significant because it reorients the process of identity formation from an external caregiver toward a sibling dynamic. In other words, the "self" is being formed not in isolation but through the mirrored experience of another. As twins become increasingly intertwined at this early stage, their experiences of selfhood, autonomy, and differentiation begin to take shape in a relational context rather than an individual one.

Ego Boundaries and Differentiation of Self

The implications of this twin bonding process raise important questions about ego boundaries and the capacity for differentiation. Ragelienė & Justickis define differentiation of self as the ability to separate oneself psychologically and emotionally from others, a process that may be uniquely complicated in twin relationships[6]. Amani & Shariatipour (2021) note that the relationship between twins is one of the most intimate interpersonal bonds, with identical twins in particular forming even closer connections than non-identical twins. This deep entanglement, beginning around 36 months, means that by adolescence, twins may experience heightened identity diffusion, struggling to establish clear distinctions between themselves and their sibling.[7]

Identity diffusion is a term introduced by psychologist Erik H. Erikson to describe a state during adolescence where an individual has not yet developed a clear sense of personal identity or future direction. This stage is marked by a lack of commitment to goals, values, or beliefs, leading to uncertainty about one's role in society. Erikson identified this as a critical phase in his theory of psychosocial development, emphasizing that successful navigation through this period is essential for forming a cohesive self-concept.[8]

Building upon Erikson's framework, psychologist James Marcia expanded the concept by categorizing identity development into four statuses: identity diffusion, identity foreclosure, identity moratorium, and identity achievement. In the context of identity diffusion, Marcia described individuals who neither explore various identity options nor make definitive commitments, often resulting in a fragmented sense of self and difficulties in decision-making.[9]

In twin relationships, the phenomenon of identity diffusion can be more pronounced due to the intertwined nature of their development. The close bond between twins may complicate the differentiation process, making it challenging for each individual to establish a distinct identity separate from their sibling. This dynamic can lead to increased identity diffusion, as the process of self-definition is influenced by the constant presence and comparison to the twin counterpart.

If Thomas’s primary relational experience was formed in such an intertwined way, how did this affect his sense of self as distinct from another? How did he navigate his own "I" apart from the "Thou" of his twin?

For twins, identity often develops through contrast—one may take on a dominant role while the other becomes more passive; one excels in certain areas while the other is expected to complement those strengths[10]. This dynamic isn’t just a personal experience; it’s shaped by how others perceive and reinforce these roles. Research shows that twins form incredibly close bonds, which can make it harder for them to establish a strong sense of individuality[11]. As they grow, breaking away from that shared identity isn’t always smooth. Independence often brings tension, even conflict, especially if one twin reaches puberty before the other, causing differences in self-image and development. Parents in these situations recognize the challenge—society encourages individuality, yet twins, particularly identical twins, may struggle more with finding their own path. How parents guide this process plays a huge role in whether twins develop a clear sense of self or remain caught between personal identity and their twinship. Ragelienė & Justickis highlight that authoritative parenting—marked by both guidance and warmth—supports differentiation and identity development, while authoritarian or permissive parenting styles contribute to identity diffusion[12].

In ancient Hebrew culture, child-rearing placed strong emphasis on shaping a child’s role within the covenant community. Proverbs 22:6—"Train up a child in the way he should go, and when he is old he will not depart from it"—reflects this approach. While this training provided a structured identity within the faith, for someone like Thomas, who already existed within a relationally enmeshed identity as "the Twin," how might this have complicated his sense of independent faith, belief, and certainty?

Theological Implications: Thomas’s Identity and Faith Journey

If Thomas’s earliest experiences were shaped by being part of an inseparable "we" rather than a distinct "I," this could explain why his faith journey in John’s Gospel is so deeply personal and marked by tension. When we look at the key moments where Thomas speaks, we see a disciple who wrestles openly with faith, demands clarity, and ultimately arrives at the most intimate confession of Jesus' divinity.

1. John 11:16 – Thomas chooses loyalty over certainty, expressing willingness to go and die with Jesus, even if his statement carries resignation. This could reflect an identity formed in partnership—going because that is what one does when bonded to another.

2. John 14:5 – He is the only disciple who verbalizes uncertainty, asking Jesus to clarify where He is going. His need for explicit answers could stem from a life of shared experiences, where direction was often clear because it was taken alongside another.

3. John 20:24-29 – He refuses to believe unless he personally experiences Jesus' wounds. In this moment, Thomas is forced into an individual faith decision—not one formed in the collective, not one affirmed by the group, but one that must be his own.

Thomas’s journey could then be seen as theological individuation—a movement from relational dependence to personal revelation. If his twinship shaped his identity early on, then John’s Gospel presents his faith journey as a necessary process of differentiation—not just from doubt to belief, but from a shared experience of faith to an intimate, independent confession: "My Lord and my God!" (John 20:28).

What This Means for Us

Thomas’s experience reminds us that the way we see ourselves shapes how we see the world. His name, his struggles, and his journey are not incidental; they reflect a process that many of us navigate in different ways. Whether shaped by family roles, societal expectations, or relational bonds, we all face the challenge of becoming fully ourselves—of moving from inherited beliefs to deeply personal convictions.

John’s Gospel does not simply present Thomas as a doubter; it invites us into his existential and theological struggle—a struggle that many of us recognize in our own journey toward faith.

Thomas’s story is far from over, and neither is ours. If Part I has revealed the shaping forces behind his identity—the twinship, the psychological tensions, the struggle for self-definition—then Part II will explore how these forces come to bear on his faith. What happens when someone whose identity has been so intertwined with another must stand alone in belief? How does Thomas’s need for certainty, shaped by his relational past, impact his response to the risen Christ? And what can his journey teach us about our own movement from questioning to conviction? In the next installment, we will follow Thomas from the framework of identity into the realm of faith—where doubt and devotion are not opposites, but companions on the path to seeing clearly.

[1] ὁδός, οῦ f: a general term for a thoroughfare, either within a population center or between two such centers—‘road, highway, street, way. Johannes P. Louw and Eugene Albert Nida, Greek-English Lexicon of the New Testament: Based on Semantic Domains (New York: United Bible Societies, 1996), 17.

[2] Andreas J. Köstenberger, John, Baker Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2004), 331.

[3] Malahat Amani and Arefeh Shariatipour, “Comparison of Self-Differentiation and Identity Statuses in Twins and Nontwins,” Twin Research and Human Genetics 24, no. 4 (2021): 176, https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2021.28.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Tija Ragelienė and Viktoras Justickis, “Interrelations of Adolescent’s Identity Development, Differentiation of Self and Parenting Style,” Psichologija 53 (2016): 24.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Kendra Cherry, “Identity vs. Role Confusion in Psychosocial Development,” Verywell Mind, last modified December 4, 2023, https://www.verywellmind.com/identity-versus-confusion-2795735.

[9] “James Marcia – Theory of Identity Development,” LibreTexts Social Sciences, accessed February 15, 2025, https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Courses/Rio_Hondo/CD_106%3A_Child_Growth_and_Development_%28Andrade%29/15%3A_Adolescence_- _Social_Emotional_Development/15.02%3A_James_Marcia__Theory_of_Identity_Development.

[10] Malahat Amani and Arefeh Shariatipour, “Comparison of Self-Differentiation and Identity Statuses in Twins and Nontwins,” Twin Research and Human Genetics 24, no. 4 (2021): 177, https://doi.org/10.1017/thg.2021.28.

[11] B. Alin Akerman and E. Suurvee, “The Cognitive and Identity Development of Twins at 16 Years of Age: A Follow-Up Study of 32 Twin Pairs,” Twin Research 6 (2003): 328.

[12] Tija Ragelienė and Viktoras Justickis, “Interrelations of Adolescent’s Identity Development, Differentiation of Self and Parenting Style,” Psichologija 53 (2016): 30.

This Part 1 is an eye opener to identity crisis we facing in this day and age. Thank you Bishop.

I'm looking forward to part II. Thank you! This blessed me.