Under-Rowing Beneath The Weight Of Glory: The Marks That Validate The Call

How Paul’s scars, suffering, and weakness became the truest proof of his apostleship. Part V

2 Cor. 4:7 But we have this treasure in earthen containers, so that the extraordinary greatness of the power will be of God and not from ourselves; 8 we are afflicted in every way, but not crushed; perplexed, but not despairing; 9 persecuted, but not abandoned; struck down, but not destroyed; 10 always carrying around in the body the dying of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be revealed in our body. 11 For we who live are constantly being handed over to death because of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be revealed in our mortal flesh. 12 So death works in us, but life in you.

13 But having the same spirit of faith, according to what is written: “I believed, therefore I spoke,” we also believe, therefore we also speak, 14 knowing that He who raised the Lord Jesus will also raise us with Jesus and will present us with you. 15 For all things are for your sakes, so that grace, having spread to more and more people, will cause thanksgiving to overflow to the glory of God.

From the very moment the exalted Christ confronted Paul on the Damascus road, the summons was not to prestige or safety but to cruciformity. His call was a summons into the same pattern of suffering, self-giving, and apparent weakness that had marked Jesus’ own life and ministry. That encounter reoriented his entire consciousness spiritually, psychologically, phenomenologically, epistemically, and ontologically. In that moment, and through the years of formation that followed, Paul came to see that to share in the glory of Christ meant also to share in His rejection, affliction, and humiliation.

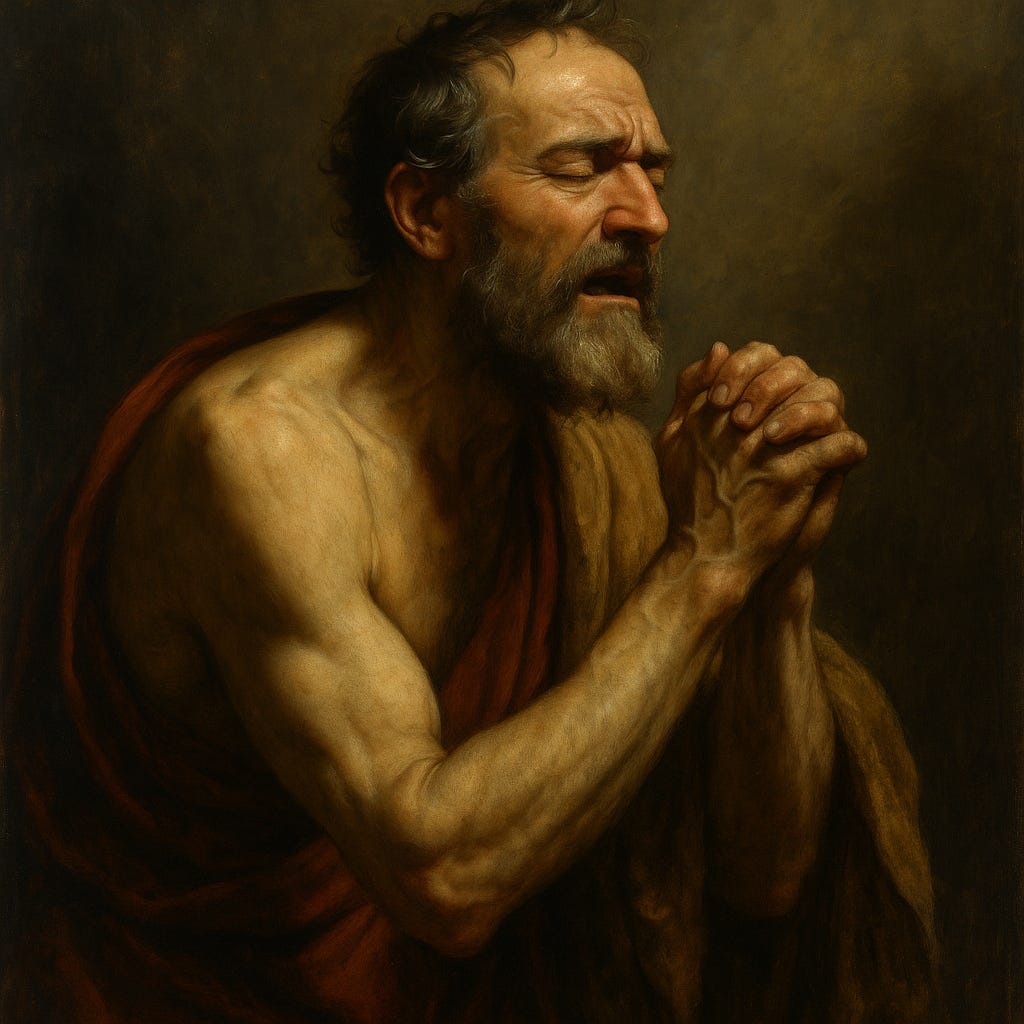

This is why Paul can describe himself as hypēretēs, an under-rower, a servant in the bowels of the ship, unseen and laboring under the weight of obedience. Apostolic grace, in Paul’s mind, was not a status to be displayed but a capacity to endure for the sake of Christ, trusting that divine power is made perfect in weakness. In 2 Corinthians 4, he names the paradox: “We are afflicted in every way but not crushed… always carrying around in the body the dying of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be revealed in our body.” His life becomes a living vessel—fragile, earthen—so that the surpassing greatness of the power might be clearly seen as belonging to God.

The same truth echoes in 2 Corinthians 12, where after describing “the extraordinary greatness of the revelations,” Paul reveals the thorn in his flesh. Whatever its precise nature, it became for him an ongoing tutor in humility, keeping him from self-exaltation. The word he heard from the Lord, “My grace is sufficient for you, for power is perfected in weakness”, became not just comfort but creed. This reshaped how he evaluated strength and success, leading him to “delight in weaknesses, in insults, in distresses, in persecutions, in difficulties… for when I am weak, then I am strong.”

In Paul’s world, apostolic grace is the lived reality of these truths. It is the spiritual and psychological resilience that grows from sustained participation in Christ’s sufferings, the phenomenological awareness that weakness can become the very place where God’s life is most visible, the epistemic humility that knows truth is not grasped from a position of control, and the ontological transformation of being conformed to Christ’s own life and death. In the final measure, Paul’s boast is not in visions or achievements, but in the marks on his body and soul that bear witness to the One who called him.

The air in Corinth is charged. Paul writes as a pastor in a strained relationship, not as a detached theorist. Cynthia Kittredge reminds us that the letter sits inside “Paul’s troubled relationship with the church in Corinth,” and that in these pages he is “defending his authority and his identity as apostle.” He works with “apologetic and polemic” at once, “both defending and attacking.” The intensity raises a homiletic choice even now. Do we match the edge of Paul’s rhetoric or de-escalate it for the sake of our listeners. Kittredge names the tension without resolving it, because Paul himself inhabits it.[1]

Inside that tension, the pronoun matters. Kittredge notes how the first person plural “we” moves across meanings in the letter, yet here it “is closely identified with Paul” and his coworkers. He refuses to preach himself. “We do not proclaim ourselves,” he writes, “but Jesus Christ as Lord,” and he names himself and his team “your servants for Jesus’ sake.” Kittredge catches the force of that last move. To call himself “your” slaves rather than simply “slaves of the Lord” stresses self-forgetfulness for the sake of those he serves.[2] This is the posture of a hypēretēs. The under rower does not grasp for titles. He bows his life toward the ones in the boat.

Eugene Teselle marks a shift in the argument. “While the focus had been on the Spirit, it now shifts to Christ.” He becomes the center, “the only one who can be called ‘the image of God’ without qualification,” the face that “permanently reflects the glory of God.”[3] Whatever grandeur was once imagined for Adam now moves to Christ. Teselle notes that Paul refuses the speculations. Adam is not a path back into glory. Christ is the path, and it runs through obedience that heals the human bond with God.[4]

How do we gain access to that face. Kittredge answers with Paul. Only through the gospel. “The entire story of Jesus, climaxing in his death and resurrection.” Paul even admits that “his gospel” as he proclaims it “may be veiled” on account of unbelief. The contrast is sharp in the paragraph. The “god of this world” blinds. God speaks light into hearts. Kittredge hears deliberate biblical echoes in Paul’s wording. “Let light shine out of darkness” reaches back to creation and to the promise of light for people who walk in deep darkness. The quotation is inexact on purpose. It opens a range of connotations that holds both creation and Messiah. The result is not a mood. It is illumination that lands with “intensity and directness” in the heart.[5]

From there Paul reaches for the image that refuses to flatter us. “We have this treasure in clay jars.” Kittredge hears the irony. “Treasure” names value and permanence. “Clay jars” name fragility and disposability. The point is explicit. “In order that” the power may be shown to be God’s and not ours. This joins what Teselle underscores. The image pushes back on the “superlative apostles” who would never call themselves clay. “Earthenware jars,” he notes, were “purely utilitarian,” not repaired but thrown away. To leaders who sell polish as holiness, Paul answers with a cracked pot that leaks resurrection.[6]

Then comes the cadence we know by heart. “Afflicted in every way but not crushed. Perplexed, but not despairing. Persecuted, but not abandoned. Struck down but not destroyed.” Kittredge hears the ancient rhetorical pattern here. Philosophers listed hardships to claim credibility. Jewish writers named righteous suffering at the hands of the faithless. Paul stands in both streams, yet he will not pretend invulnerability. He “admits his feelings of despair,” Teselle says, and names endurance as gift “from God.”[7] Kittredge presses the language further. Paul speaks of “carrying in the body the death of Jesus.” The word is rare - Nekrōsis. Not a single event. An ongoing process of dying. Its purpose is clear. “That the life of Jesus may also be made visible in our bodies.” Verse eleven says it again and repeats “be made visible.” The verb “being given up to death” ties the apostles to the story of Jesus.[8]

This is where the under rower returns. Authority does not rest on ecstatic experience or private illumination alone. Kittredge points to the juxtaposition of “ecstatic and joyful visionary experience” with “relentless hardships.” The vision transfigures. The hardships transform. “The extraordinary power of God in their midst is contained in weak clay jars.” Not only does the dying of Jesus change the ones who carry it. It becomes revelation for those who watch weakness and power appear together in the daily work of the ministry.[9] In our moment, shaped and seduced by consumer hunger, that combination is either dismissed as extreme or marketed as a brand. Paul will have neither. The treasure is Christ. The jar is common. The life that shows through the cracks is the proof that God is at work.

Paul’s vision of apostolic life is inseparable from what Adrian van Kaam would call the “transcendent dimension”, the God-given capacity that breaks the closed loop of self-referential living. Van Kaam observed that this dimension is “the gifted disrupter of what could be a closed system of reactivity,” creating “a rupture between impulse and reaction” so that we are “freed to listen to that which is beyond our sociohistorical pulsations, our vital pulsions, and our functional ambitions.”[10] This is the space where the self, instead of simply reacting out of ingrained patterns, can respond in freedom to God’s call.

For the under-rower, this rupture is essential. Without it, the oar is driven by reflex, by the pull of cultural currents, by the momentum of survival or ambition. With it, each stroke can be chosen in obedience to the One who calls. Van Kaam insists that such “distancing makes it possible for one to apprehend and affirm life as more than vital-functional reactivity,” so that one’s responses are shaped by “memory, imagination, and anticipation” formed through the Spirit.[11] This comports exactly with Paul’s description of “not proclaiming ourselves,” for it locates our action not in the heat of self-assertion, but in the reflective, Spirit-mediated posture of service from below.

Van Kaam also names the reality that, left to ourselves, we cannot fulfill our deepest calling: “People discover that their own unaided powers are unable to attain the fulfillment of their spiritual aspirations… He sends his own Son to help humanity overcome the Fall’s consequences for human formation… Insofar as our life of transcendent formation is the gift of the Holy Spirit, we call it a life of pneumatic transformation.”[12] This is under-rowing in its clearest theological light. The one beneath the deck knows he does not supply the wind; he does not own the vessel. His task and his freedom are to take his place in the movement of Another’s design, in the power of Another’s Spirit.

The “treasure in clay jars” image presses further into the psyche. Depth psychology recognizes that the human person is a fragile, finite container for an animating reality it does not originate. Paul names this without shame. He refuses to deny the cracks or disguise the vessel. This is what Jung would have called the integration of shadow, the acceptance of what is vulnerable, impermanent, and limited in the self, not as a disqualification for vocation but as the very site where the treasure can be seen for what it is. To repress the cracks is to block the light; to admit them is to let the life of Jesus be “made visible” in mortal flesh.

Jung warns that ignoring these inner realities does not dissolve them: “We think we can congratulate ourselves on having already reached such a pinnacle of clarity, imagining that we have left all these phantasmal gods far behind. But what we have left behind are only verbal spectres, not the psychic facts that were responsible for the birth of the gods. We are still as much possessed by autonomous psychic contents as if they were Olympians… The gods have become diseases.”[13] In other words, what we refuse to acknowledge in ourselves becomes the hidden master of our actions, whether in the nervous system, in our compulsions, or in the collective eruptions of whole societies.

The under-rower cannot afford such blindness. To labor unseen in obedience to Christ demands a willingness to face the inner pantheon of compulsions and fears, to name the forces that would otherwise steer the oar from the shadows. Paul’s refusal to mask his fragility, his cataloging of hardships, is not morbid confession; it is the active choice to keep the helm in the hands of the One whose power is made perfect in weakness, rather than in the grip of unacknowledged “autonomous psychic contents.”

Paul’s knowing of the gospel is not the detached posture of a spectator. It is a lived, participatory knowing, grounded in the tradition he openly professes and carries forward. Michael Polanyi insisted that “each of us must start his intellectual development by accepting uncritically a large number of traditional premises of a particular kind,” and that our progress will “always remain restricted to a limited set of conclusions which is accessible from our original premises.”[14] Paul’s gospel is not a self-generated “universal truth,” but the received message of the crucified and risen Christ, shaping his thought, ministry, and endurance from the start.

Polanyi argued that belief in transcendent obligations such as truth, justice, and charity “can… be upheld now only in the form of an explicit profession of faith,” sustained by traditions which embody such professions.[15] Paul’s confession that “we do not proclaim ourselves, but Jesus Christ as Lord” is precisely such a profession, rooted in the apostolic tradition. For Polanyi, the purpose of a dedicated society is to “enable its members to pursue their transcendent obligations,”[16] which is also the purpose Paul assigns to the church, to live for the glory of God, not for self-promotion or worldly gain.

Polanyi defined reality as “that which is expected to reveal itself indeterminately in the future.” To hold the gospel as true is to trust that it will manifest itself in “an indeterminate range of yet unknown and perhaps yet unthinkable consequences.”[17] Paul’s under-rower obedience is sustained by this expectation, he rows in rhythm with a reality he cannot fully predict but knows will continue to reveal Christ’s life in him and through him.

All explicit knowing, Polanyi explains, is grounded in the “tacit dimension,” which has a “from–to” structure: we attend from subsidiary elements to a focal whole.[18] He illustrates this with the craftsman’s hammer: “When we use a hammer… we do not feel that its handle has struck our palm but that its head has struck the nail… They are not watched in themselves; we watch something else while keeping intensely aware of them.”⁴ In Paul’s ministry, the “subsidiary” realities, his afflictions, perplexities, and endurance — are not the focus, yet they are what enable the Corinthians to perceive the focal reality: “the life of Jesus… revealed in our mortal flesh” (4:11).

Polanyi warns that if focal attention shifts to the subsidiary elements, the performance breaks down: “All particulars become meaningless if we lose sight of the pattern which they jointly constitute.”[19] The Corinthians risked doing exactly that by judging Paul on appearances, eloquence, or immediate results. Losing sight of the whole (the gospel embodied in weakness) would strip the parts of their meaning.

Polanyi distinguishes between “representative” meaning, which points beyond itself, and “existential” meaning, which is intrinsic to the thing as part of a whole.⁵ Paul’s “clay jar” is like that. The jar’s worth is not in drawing attention to itself (representative) but in fulfilling its role within the whole, holding the treasure and revealing it through its very fragility (existential). That is the way of the under-rower: the vessel matters because it carries the life of Christ forward, in service to the One who established it.

Paul speaks to the Corinthians as one who has taken his place at the oar. His ministry is not self-generated or self-directed; it is carried forward inside a tradition that has claimed him. Lesslie Newbigin describes how “a vast amount of our culture—its language, its images, its concepts, its ways of understanding and acting… is not something we look at, but something through which we look.”[20] An under-rower doesn’t scan the horizon from the captain’s chair; he sees his work and his world through the framework of the ship he serves. Paul’s framework has been remade in Christ, and now “the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” is the lens through which he sees, rows, and calls others to row.

Newbigin draws the parallel with the scientific enterprise, which “begins from the conviction that the universe is accessible to rational understanding” and can only advance when its members “accept the authority of the tradition… as the necessary precondition for gaining… [a personal] grasp of the truth.”[21] The under-rower’s authority is like this. Paul does not “proclaim [him]self” (4:5) because his ministry is bound to the apostolic gospel, a tradition he indwells and to which he submits. He rows in step with what he has received.

Learning to row in that tradition requires trust. “He has to trust the tradition and trust the teacher as an authorized interpreter of it… There is no alternative to this.”[22] An apprentice oarsman begins by matching his stroke to the veterans around him; a disciple begins by trusting those who first set the pace. Paul’s aim is that the Corinthians will grow into the point where they can say, “Now I see… Now I know the Lord Jesus Christ,” not as a private opinion, but as “the truth which is true for all.”[23]

Newbigin dismantles the idea of a neutral perspective: “Every exercise of reason depends on a social and linguistic tradition,” and there is no “disembodied ‘reason’ which can act as impartial umpire” between rival claims.[24] In Corinth, rival “plausibility structures” were shouting contradictory orders into the crew. The culture prized eloquence, status, and visible strength.

Through that lens, a scarred and weary apostle looked like a liability. But the gospel’s lens interprets the same facts as signs of God’s power in weakness. “Facts,” Newbigin reminds us, “are always theory-laden.”[25] In the rowing room, the same sound might be heard as either the rhythm of the oars or the groan of exhaustion, depending on the ear that listens.

To learn the gospel’s way of hearing and seeing, the Corinthians must acquire what Newbigin calls a “second first language.”[26] A tourist learns a few words to get by; a crew member learns the language of the ship until the orders are part of him. The Corinthians must stop translating the gospel back into the categories of their social world. They must think, speak, and live in the grammar of the cross, “always carrying in the body the dying of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be made visible” (4:10). That is the cadence of the gospel stroke.

Traditions, Newbigin says, are tested “for their… capacity to lead their adherents into the truth.”[27] An under-rower’s worth is proven in the progress of the ship under the captain’s command. Paul offers his life as such proof: the gospel he rows for is moving God’s purpose forward, revealing Christ’s life through his mortal flesh. His scars are not a break in rhythm but the marks of faithful service.

The Corinthians’ temptation is to misinterpret the rhythm, to break stroke with the crew, to row by the beat of another master. Newbigin’s point about “public truth” is the safeguard: the faith “must… be publicly affirmed and opened to public interrogation and debate” because it is “the truth which is true for all.”[28] The under-rower’s labor is hidden below deck, but it is ordered toward the public arrival of the vessel at its appointed harbor. Paul rows so that the treasure will reach those for whom it is intended, and he calls the Corinthians to pull with him, in time, in tune, in trust.

Paul’s words carry more than they can hold. “Afflicted in every way but not crushed. Perplexed, but not driven to despair. Persecuted, but not abandoned. Struck down but not destroyed.” He is not offering tidy contrasts. He is describing a life flooded by Christ’s presence. Jean-Luc Marion calls this a saturated phenomenon, where “intuition is given to a degree that always outruns intentionality,” a givenness that comes with “overwhelming magnitude” that no ready-made concept can contain.[29] The gift keeps giving, faster than the mind can measure. Paul lives there. The more the blows land, the more the life of Jesus shows.

Marion says the saturated phenomenon “exceeds the categories and the principles of understanding, it will therefore be invisible according to quantity, unbearable according to quality, absolute according to relation, and incapable of being looked at according to modality.”[30] That is what Paul sounds like. He reports conditions no analysis can domesticate. “Always carrying in the body, the dying of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus may also be made visible.” The jar is cracking, yet the treasure shines. Affliction does not cancel the gift. It becomes the place where the gift appears.

Marion speaks of paradox as the posture where this kind of manifestation happens. At the point of “bedazzlement… when perception passes beyond its subjective maximum,” the subject cannot stand over the gift. He is held by it.[31] That is Paul under the oar, breathing inside a mystery that holds him fast. He does not control the cadence. He receives it. The paradox is not solved. It is inhabited.

Marion’s icon helps us name the intimacy of this encounter. The icon looks back at us. Its gaze “cannot be prevented, stopped, or contained.”[32] Paul rows under that unblinking regard. Christ sees him, names him, sustains him. The gaze does not lift when the storms rise. It does not dim when the lamps go out. It orders each pull and keeps the rhythm when strength is thin. Paul is not mastering the presence. The presence is mastering him.

Marion’s event also clarifies the texture of Paul’s days. The event gives itself with “unrepeatability” and “unforeseeability,” leaving behind an “infinite hermeneutic.”[33] Damascus was such an event. So were the nights in prison, the beatings, the fastings, the shipwrecks. None of them are mere data points. Each one arrives as a counter-experience that turns Paul inside out and shows that Christ is here. What looks like loss yields gain. What feels like death becomes the place life breaks through.

The register of the flesh reaches even nearer. Marion describes the flesh as unsubstitutable, a site of “auto-affectivity” where agony and desire are known from within. “Nobody can enjoy or suffer for me.”[34] Paul knows this truth in his scars. “I bear in my body the marks of Jesus.” He does not speak about pain from the veranda. He speaks as one who has carried the dying of Jesus in his own flesh, and has found there, to his surprise, that the life of Jesus is being made visible.

Even the idol and the icon distinction helps the church read a life like this. An idol is content I handle and frame. An icon handles me. Paul’s ministry is not a spectacle he curates. It is an icon that sees. The gaze falls on him and then through him onto the communities he serves, so that “the light of the knowledge of the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ” becomes their light as well.

Marion’s Eucharistic insights give a sacramental image for what is happening in Paul’s body. In the sacrament, the visible gives what it does not appear to give. “Bread become body, wine become blood,” given “to the point of abandonment,” in a form that “the senses cannot master,” where “the invisible is translated, surrendering itself and abandoning itself in the visible to the point of appearing insofar as the invisible remains.”[35] Paul is a living chalice of that same logic. Outwardly, he wastes away. Inwardly, he is renewed. The vessel is common clay. The treasure is not. Weakness, which looks like lack, gives what it does not appear to give. It gives the life of Jesus for others to see.

Marion speaks of a “saturation of saturation.” Creation is gift. Redemption is the greater gift where love outstrips every measure of justice. He cites the confession that God’s love “is so great that it turns God against himself… [Jesus’s] death on the Cross is the culmination of that turning of God against himself in which he gives himself in order to raise man up and save him.”[36] Paul rows inside that double gift. First life given. Then life remade in the Crucified. The conatus to preserve the self yields to the radiance of a Presence often known as absence. The more he is poured out, the more the treasure fills the frame.

All of this is governed by givenness. “Givenness alone is absolute, free and without condition, precisely because it gives.”[37] The point of the reduction is to let the thing show itself “as on a screen,” where a “double visibility” appears at once. First, the given itself. Second, the visibility of “l’adonné,” the gifted one who is seen in the seeing.[38] Paul’s language already bears this shape. There is the treasure and there is the jar. There is the life of Jesus and there is the mortal flesh. There is the given Christ and there is the under-rower whom Christ’s gift has made.

An under-rower lives by what is received. The cadence is not invented. It is heard. The strength is not gathered from private stores. It is supplied in the pull. The course is not set from below deck. It is trusted. This is why Paul can say, without embarrassment, in the same breath, that he is pressed from every side and yet not crushed. The saturation holds him. The gaze keeps him. The event carries him. The flesh bears its truth and finds Another there. And the church, beholding a jar that should have shattered long ago, learns again to name the treasure for what it is.

Paul’s final words in this chapter lean on an older voice: “having the same spirit of faith… I believed, therefore I spoke.” The line comes from Psalm 116, a psalm of lament and deliverance. It is not shouted from a safe distance but uttered in the middle of trouble: “I am greatly afflicted… I said in my alarm, ‘All humanity is a lie.’”[39] The psalmist believes and speaks while naming the unreliability of human assurances, because the Lord has “delivered my soul from death, my eyes from tears, my feet from stumbling.”[40] Paul claims that same spirit, the courage to keep speaking when the air still smells of alarm, as the posture that has carried him through every paradox he has named.

This is not faith as an abstract statement; it is an event in consciousness, a lived act that reorders perception in the moment. Tillich insists that “faith precedes all attempts to derive it from something else”[41] it cannot be reduced to fear or survival instinct, because those analyses already lean on faith to function. In Psalm 116 and in Paul’s own life, the act of believing is a response to God’s givenness, a reality that comes on its own terms and resists being mastered. Like an under-rower hearing the cadence from above, Paul does not create the rhythm; he receives it and keeps time with it.

This is the self confronting its own finitude. Alarm and disillusionment can fracture the ego, yet in that rupture the self can encounter the unconditional. Tillich says faith is “certain in so far as it is an experience of the holy,” but “uncertain in so far as the infinite… is received by a finite being.”[42]Accepting this tension “is courage.”[43] In Paul’s case, that courage is not an abstract virtue, it is the willingness to keep pulling at the oar when every muscle is burning, trusting the one giving the call even when the deck above is shouting conflicting orders.

Paul’s “I believed, therefore I spoke” reveals a way of knowing that is participatory. In Polanyi’s terms, he attends from the subsidiary realities of affliction, perplexity, persecution, and blows to the focal reality of God’s faithfulness. This “from–to” structure makes faith not just a content to hold but an integrated act of perceiving and responding. Speaking is part of the knowing, the articulation of what has been perceived in trust.

Tillich names the risk: “Ultimate concern is ultimate risk and ultimate courage.”[44] The only certainty is the ultimacy of ultimacy itself; the concrete content, even the God one names, is embraced in risk. If it proves less than ultimate, the self can collapse. Paul knows this: if Christ is not raised, the rowing has been in vain. But faith does not wait for all risk to be removed; it takes the stroke because the One giving the cadence has already conquered death.

So, Paul rows on, under the same spirit that moved David to speak in his alarm. He does not deny the unreliability of men; he names it and keeps speaking. He does not eliminate uncertainty; he accepts it as the place where courage shows itself. He does not row because the sea is calm; he rows because the Captain has proved true. This is how the paradox of being “afflicted… but not crushed” finds its final cadence, believing, therefore speaking...until the harbor is in sight.

[1] Cynthia Briggs Kittredge, “Exegetical Perspective on 2 Corinthians 4:5–12,” in Feasting on the Word: Preaching the Revised Common Lectionary: Year B, ed. David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor, vol. 3 (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 87.

[2] Kittredge, “Exegetical Perspective on 2 Corinthians 4:5–12,” 88-89.

[3] Eugene Teselle, “Theological Perspective on 2 Corinthians 4:5–12,” in Feasting on the Word: Preaching the Revised Common Lectionary: Year B, ed. David L. Bartlett and Barbara Brown Taylor, vol. 3 (Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 2009), 87–88.

[4] Kittredge, “Exegetical Perspective on 2 Corinthians 4:5–12,” 88-89.

[5] Kittredge, “Exegetical Perspective on 2 Corinthians 4:5–12,” 88-89.

[6] Teselle, “Theological Perspective,” 89.

[7] Teselle, “Theological Perspective,” 90.

[8] Kittredge, “Exegetical Perspective,” 90–91.

[9] Kittredge, “Exegetical Perspective,” 91.

[10] Rebecca Letterman and Susan Muto, Understanding Our Story: The Life’s Work and Legacy of Adrian van Kaam in the Field of Formative Spirituality (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 2017), 126–128.

[11] Letterman and Muto, Understanding Our Story, 126-128.

[12] Letterman and Muto, Understanding Our Story, 140-141.

[13] C.G. Jung, The Collected Works of Carl Jung, Volume 13, trans. R.F.C. Hull, (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1967), para. 54.

[14] Michael Polanyi, Science, Faith and Society (Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 1964), 82–84.

[15] Polanyi, Science, Faith and Society, 84.

[16] Polanyi, Science, Faith and Society, 9–11.

[17] Michael Polanyi, Personal Knowledge: Towards a Post-Critical Philosophy (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962), 74–76.

[18] Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, 76.

[19] Polanyi, Personal Knowledge, 76.

[20] Lesslie Newbigin, The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (Grand Rapids, MI; Cambridge, U.K.: Wm. B. Eerdmans, 1989), 34–35.

[21] Newbigin, Gospel in a Pluralist Society, 48.

[22] Newbigin, Gospel in a Pluralist Society, 49–50.

[23] Newbigin, Gospel in a Pluralist Society, 49–50.

[24] Newbigin, Gospel in a Pluralist Society, 53–59.

[25] Newbigin, Gospel in a Pluralist Society, 59.

[26] Newbigin, Gospel in a Pluralist Society, 53–59.

[27] Newbigin, Gospel in a Pluralist Society, 53–59.

[28] Newbigin, Gospel in a Pluralist Society, 49–50.

[29] Donald Wallenfang and Jean-Luc Marion, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist: An Étude in Phenomenology(Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2017), 105, 107.

[30] Wallenfang and Marion, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist, 107, 109.

[31] Wallenfang and Marion, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist, 111.

[32] Wallenfang and Marion, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist, 115.

[33] Wallenfang and Marion, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist, 119.

[34] Wallenfang and Marion, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist, 113.

[35] Wallenfang and Marion, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist, 121, 123.

[36] Wallenfang and Marion, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist, 127, 129.

[37] Wallenfang and Marion, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist, 131.

[38] Wallenfang and Marion, Dialectical Anatomy of the Eucharist, 133, 135.

[39] Psalm 116:10–11 MT; cf. LXX Ps 115:1–2.

[40] Psalm 116:8–9.

[41] Paul Tillich, Dynamics of Faith (San Francisco: HarperOne, 2024), 9.

[42] Tillich, Dynamics of Faith, 18–19.

[43] Tillich, Dynamics of Faith, 18–19.

[44] Tillich, Dynamics of Faith, 21.

This is very heavy. I read this when you posted it and it hit me in numerous ways. This is all very true and anyone who bares battle scars would almost fully understand this.

The last paragraph is loaded with heavy information that leaves one thinking about the sight of the harbour and knowing the one who promised to be true and faithful.